Malternatives Part 2: Cognac & Armagnac 101

A Whisky Lover’s Overview

The Old Guard

We continue our ‘Malternatives’ series with spirits I personally find fascinating, and very close to my French heart. It follows on from my Rum 101 feature. You can find it here. In this second part, we’ll take a look at - cue in La Marseillaise - Cognac & Armagnac.

Both are produced in the south-west of France: Cognac around the cities of, well, Cognac, but also Segonzac, Saintes, and La Rochelle, which means basically around the Charente river; and Armagnac in the province of the same name, towards the Gers region, aka Rugby Country, and the cities of Eauze, Condom (yes, for real, and no, you’re not pronouncing it well), and Auch.

Both are actually similar at first look, as they are, in fact, brandies made from distilled white wine and aged in French oak casks. The differences only appear when you take a closer look, although we’ll see that different taste profiles also are very much due to the producer’s choices throughout the whole process.

A Quick Look at the History

Our story starts with Armagnac first, which is claimed to be the oldest distilled spirit made for consumption and still produced today. During the Arab conquest of the Iberic peninsula - 8th century - a number of middle eastern inventions made their way to Europe, including the alambic; the French word for a still and derived from the Arab language - Al-ambiq.

There are accounts of distillation being carried out in eastern Europe as early as the Middle Ages, but the first official documents point to the 14th century around the Armagnac region. Vital Du Four, a monastic scholar, wrote a medicine treaty in 1310 titled “Very useful book to keep healthy and stay in good shape” - again, for real - in which he listed the “40 virtues of the brandies from the counties of Eauze and Saint-Mont”. Said Eau-de-vies - or Aygues Ardentes (burning waters) as they were called at the time - would restore movement to paralysed limbs if applied on them, cure headaches when massaged on the head and, my favourite, “if kept in the mouth, it unbinds the tongue and gives boldness to shy persons who drink it sparingly”. Reminds me of high school.

At the time, not unlike early accounts of whisky, or Uisge Beatha, it was both used as medicine and consumed unaged, often flavoured with herbs and botanicals. In parallel, vineyards slowly grew in size in the following centuries and, at the turn of the 16th century, Dutch merchants who were trading along the French southern Atlantic coast started importing white wine from there.

They moored in seaside ports like La Rochelle for Cognac or Bayonne for Armagnac, and bought wine in barrels to be distributed in Europe’s northern ports. This is when distillation of wine really took off, as it offered the benefit of concentration of volume, thus a higher volume of alcohol per ship, and also helped in the conservation and stabilisation of white wine when added to it in small quantities. The Dutch called the Eau-de-vie Brandewijn, or “burnt wine”, which of course later gave us the word brandy. They often consumed it mixed with water, thinking they could recreate the original wine.

Cognac soared in popularity at around the same time and for the same reasons. While there have been vineyards in much of France since Roman times, it’s only when the Dutch merchants came to dry the Poitevin marshlands that they started buying white wine from the region, which helped to grow its reputation. At the turn of the 18th century, at the height of the British Empire’s influence, London became the primary destination for Cognac, solidifying its reputation. British and Irish nobles started investing in Cognac and, like Scotch and its whisky barons, many of the big names you see today date back to the 18th and 19th century and were originally British investors: Hine, Hennessy, Martell, or Delamain to name but a few.

It’s also around this time that people started to notice that a prolonged stay in barrels - which were used only as storage and transport vessels - could round out the spirit and give it additional flavours, so much so that people started to drink it neat rather than diluted. It became customary for Cognac and Armagnac to be aged in wood for a few months or years, depending on the level of quality that the producer aimed for. It was also often slightly sweetened to make it more palatable.

Towards the late 19th century, Cognac started to be exported in bottles rather than casks and its popularity, both overseas and in Parisian bars, was soaring until the worst disaster in the history of European viticulture: the Phylloxera crisis.

Phylloxera is a parasite bug native to the Americas. It arrived by ship in France in the second part of the 19th century: 1879 for Cognac and 1893 for Armagnac. This small bug lives in the dirt and eats the vine roots. It was previously undetected as American vine species are immune to it. Vitis vinifera though, from which all winemaking vine plants are derived, is not. At the turn of the 20th century, a considerable part of the French vineyards was decimated. This helped propel alternatives such as Whisky and Absinthe onto the big stage, as substitutes were needed.

A solution was eventually found by grafting European grape varieties onto American vines, making them resistant. But the majority of the vineyards had been uprooted to be turned into cereal farmland and, still to this day, the surfaces allocated to vineyards in these two regions are much smaller than they once were prior to Phylloxera. As an example, Armagnac at its peak in the 1880s represented roughly 100,000 hectares of vineyards, whereas the current surface allocated to its production is roughly fifty times less.

Furthermore, the 20th century was packed full of events for these two regions. Firstly, in 1936, the French government created what is now known as INAO, the official institute tasked with creating and managing the AOCs (Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée) for French agricultural products. On the 15th of May, 1936, the first six appellations were created: five for wines (Châteauneuf-Du-Pape, Tavel, Cassis, Arbois and Monbazillac), and a sixth for Cognac. Armagnac was officially regulated in the same way later that year.

After the second world war, Cognac established itself as a luxury drink, whereas Armagnac, due to a lack of strong brands and distribution networks, eventually fell into the category of “old man drinks” and lost momentum. As brown spirits became less and less fashionable, many Armagnac producers uprooted their vines once more, or changed grape varieties in order to produce IGP wine, often not memorable but easier to sell. Cognac fared well until the 1990s, when overproduction and economic crisis in Asia forced producers to reduce the vineyard surfaces.

The end of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st saw a surprising surge in Cognac exports, especially toward the USA where, surprisingly, rappers were making it their drink of choice, calling it “yak”. This made it the de facto African-American drink, standing seemingly in opposition to whiskey - especially bourbon - which had the image of being a white anglo-saxon protestant libation of choice. This gave Cognac a massive sales boost, and continues to do so. Truthfully though, only for the major brands, as these bottles are often consumed at parties or in nightclubs mixed with coke or ginger beer, thus needing to be cheap and consistent.

These days, things continue to be tough for Armagnac producers, as they still lack the infrastructure and communication capabilities to be able to turn it into a widely enjoyed drink. Cognac survives thanks to the export market, which represents roughly 98% of its sales. That’s right, only 2% of Cognac is consumed in France, which is a massive shame if you ask me. That said, if you aren’t French and have been drinking Cognac, well, thank you for keeping the boat afloat.

The so-called cocktail renaissance of the early 2000s, which saw the rise and resurgence of quality-oriented cocktail bars in the US first and then around the globe, is one way for those spirits to reestablish themselves as bar staples. A big part of this renaissance was bartenders unearthing and researching ancient cocktail recipes from the 19th and early 20th century, and a lot of those featured Cognac in some way such as Vieux Carré, Sidecar, Sazerac and Horse’s neck.

Heading into the 2010s, these trendy cocktail bars became more focused on developing their own recipes, and finding unique and interesting spirits to base those drinks on was one way to set your bar apart from others. Sensing this, Armagnac producers added a new category to the AOC in 2014, the Blanche d’Armagnac; i.e. unaged spirit, mainly meant to be used in cocktails.

Cognac and Armagnac are also the base of many liqueurs, like the famous Grand Marnier, an orange liqueur. Producers also often make Floc de Gascogne (for the Armagnac appellation region) or Pineau des Charentes (around Cognac). Both are mistelles, which means they are produced by adding young spirit (at least 1 year old) to unfermented grape must. They are then aged in cask for at least 6 or 12 months depending on the appellation. However, some are aged much longer, sometimes for decades, and can be of tremendous value as dessert wines. Try pairing them with strong blue cheeses or a pecan pie!

Production

Cognac

Cognac nowadays represents roughly 73,000 hectares of vineyards (155,000 acres in freedom units). A few different white grape varieties are allowed within the AOC, but the overwhelming majority of spirits are distilled from Ugni Blanc (also known as Trebbiano Bianco in Italy) though, prior to Phylloxera, the prevalent variety was Folle blanche.

There are different sub regions, called Crus in the Cognac appellation:

Grande Champagne: 34,000ha around the city of Segonzac (not all planted in vineyards though). It has the reputation of producing the best eaux-de-vie, fit for aging more than 50 years, thanks to the thick bed of tender Cretaceous limestone and thin soil.

Petite Champagne: 15,000ha occupied by vineyards, south of the city of Cognac, around the town of Jonzac. The quality is also very high, but placed second in the ranking because of a less thick limestone bed. A blend of Petite and Grande Champagne Cognacs containing at least 50% Grande Champagne can be labelled as Fine Champagne (pronounced ‘feen champagne’).

Borderies: Named like this because it borders the city of Cognac, on the northern bank of the Charente river. It is the smaller sub region in Cognac - only 5% of the total production - and produces sought after brandies that typically exhibit violet aromas. The Cognacs produced there have a reputation for quicker maturation due to their floral and fruity quality.

Fins Bois: The biggest area of production, accounting for roughly 40% of the volume of produced Cognac, it is a region located between the towns of Angoulême, Saint-Jean-d’Angély and Saintes.

Bons Bois: While this cru doesn’t have the best reputation of all, one can still find beautiful Cognacs hailing from there. They tend to be fuller bodied and less elegant as the Champagnes, but age more quickly, and can offer tremendous value. As with whisky, it’s not all about the place where it is made, but also who makes it.

Bois Ordinaires: Located next to the Atlantic coast, and even on the Ré Island, this is the least fashionable of the crus, but that doesn’t mean it's all bad. The cru classification was established based on age-worthiness. While Bois Ordinaires Cognacs won’t age as long as a Grand Champagne on average because of sandy soils, they can be beautiful, even showcasing a hint of salinity from time to time.

Any blend of these crus can only be called Cognac, and must not make mention of the crus.

Grapes are harvested from mid-September to late October, depending on the vintage, and are then fermented into low-alcohol, high-acid white wine, with an ABV of 7 to 12%. This wine is then distilled either on the lees, for a fuller-bodied spirit or filtered, for something more delicate. Distillation is permitted only up to the 31st of March of the next year, which means that the stillmen - who are also often the winemakers themselves - work on a tight schedule. That can be quite a challenge, as Cognac, like single malt, is double distilled. The stills though, called Charentais stills, are not the same shape. They have a very thin lyne arm, are almost always condensed through a “serpentin”, a kind of worm tub if you will, and they feature a “chauffe-vin”, essentially a vessel filled with wine through which the lyne arm goes, thus pre-heating the next batch of wine before it goes into the still. The still size is regulated, and must not exceed 30hL, or 3,000 litres.

After distillation, Cognac has to be aged for a minimum of two years in French oak, either of the Quercus Petraea or Quercus Robur species. The trees come from the Limousin and Tronçais forests. Limousin oak has more of a coarse grain, which will give structure to the brandy, whereas Tronçais oak has a finer grain, which gives more space to the spirit for longer maturation. It is quite common for very old Cognacs to be transferred into demijohns and stored in the Paradis, a fenced-off part of the warehouse where the oldest eaux-de-vie are kept. When in demijohns, Cognac still changes over time, albeit much more subtly and slowly.

It is worth noting that cask finishing is very uncommon in both Armagnac and Cognac. Firstly, if they’re put in American oak, they lose the appellation, which greatly reduces possibilities. Secondly, aging is seen more as a way of taming and rounding out the eau-de-vie rather than a flavouring step. It is customary for young spirits to be put in new oak for a few years, and when the cellar master thinks they’re reached optimal wood extraction, they transfer them to tired casks, called fûts roux, for sometimes decades-long maturation. The goal is always to achieve balance between the spirit character and the wood impact.

Much like in whisky, there is also the distinction between a dry or humid warehouse, referred to here as wet or dry cellar. Dry cellars have a relatively low humidity content, thus allowing for more wood flavour extraction and slower alcohol evaporation, and vice versa for wet cellars, which allow for a longer and gentler aging period, favouring alcohol evaporation rather than water. Most producers use a combination of both types of cellars.

You also may have sometimes seen the term ‘early landed’. It refers to a common practice during the 19th century. Young Cognacs (1-3yo usually) would be sent in barrels to the UK, and would then be stored in wet, damp cellars under control of the British customs, only to be bottled a few years later. They were indeed sometimes called ‘Early landed, late bottled’. These maturation conditions would moderate the wood extraction, thus producing rather pale and delicate brandies. It is thought the term VSOP (Very Superior Old Pale, explained just below) appeared at this time.

These days, early landed refers to a Cognac which spent some time aging in a country other than France, 99.999% of the time: England. It has to be aged within the AOC limits for two years at least prior to being shipped abroad, and must be kept in a bonded warehouse controlled by British customs to prevent any malicious alteration of the spirit. It can then be bottled anywhere and still be called Cognac. This is a very rare practice, only Hine does it to a noticeable extent, as well as the occasional independent bottler here and there.

The Cognac industry is also structured in a very different way from whisky. You’d think that big brands like Hennessy, Martell or Courvoisier would own massive distilleries, but they don’t. They almost all own a few stills, but the overwhelming majority of the spirits they mature is purchased unaged from small, independent distillers from the whole Cognac region. These big houses usually have contracts with these producers, especially if the latter are well regarded. The big houses then age the brandies they purchase for however long they want, and blend them to achieve the profile they need for their own brands. There are smaller houses like Prunier for example, which function as bigger brands but at a much smaller scale, and bigger wine producers, like Lhéraud for example, which do not deal with the négociants and instead bottle all of their Cognac production from their vines under their own brand. Those are often better value. There is also a growing independent bottling scene, championed by Guilhem Grosperrin, who was one of the first to release cask strength, single cask, un-fiddled with Cognac.

Age mentions on Cognac bottles can be a bit confusing at first, so here’s a quick rundown:

VS / Very Special / Sélection / 3 stars: A minimum of 2 years in oak.

Supérieur: A minimum of 3 years in oak. Very rarely used.

VSOP / Réserve / Vieux: Very Superior Old Pale. A minimum of 4 years in oak.

Vieille Réserve: A minimum of 5 years in oak. Very rarely used.

Napoléon / Très Vieille Réserve / Très Vieux: A minimum of 6 years in oak.

XO / Extra Old / Hors D’Âge: A minimum of 10 years in oak.

XXO / Extra Extra Old: A minimum of 14 years in oak.

It is important to note that XO or XXO bottlings very often contain components much older than the required minimum. For example, the famous Louis XIII bottling from Rémy Martin is rumoured to contain Cognacs that are more than 100 years old.

Vintage-stated Cognacs are quite rare, as in order to be able to state the vintage, casks have to be sealed off and a bailiff has to be present every time they are sampled, moved or when they’re blended and bottled. At the expense of the producer, of course. Recently, independent bottlers and smaller producers have found a workaround: they write the last two numbers of the vintage. For example, a 1911 Cognac can be labelled as “Lot 11”, “n°11”, “v11” or anything close to that. You might ask then, how do we know it’s not a 2011 Cognac? Well, the taste first, then the price.

Armagnac

Armagnac is, on paper, the same as Cognac. But, as mentioned at the beginning of this piece, there are details in production which make it slightly different. Firstly, grape varieties.

While Cognac is 98% Ugni blanc, Armagnac can be made with up to ten grape varieties with four being vastly predominant:

Ugni blanc: Borrowed from Cognac for its resistance to diseases, high yields and high acidity. It is the main grape used, but not as ubiquitous as in Cognac.

Folle Blanche: Considered of very high quality for the production of eau-de-vie, but quite hard to grow because of how fragile it is. It makes for a floral and delicate spirit.

Baco 22A: A hybrid developed in the early 1900s as a solution for the phylloxera problem. It is only found in Armagnac and can only be used for distillation. It produces clean but powerful eaux-de-vie.

Colombard: A very aromatic variety, combining aromas of grapefruit skins, citrus and flowers with a relatively high acidity. It is ubiquitous in the Côtes de Gascogne IGP white wines produced in the region for those qualities, but more rarely used for Armagnac production. Some producers like it for its fruity aromas though, such as Chateau Arton.

Blanc Dame

Plant de Graisse

Jurançon Blanc: Don’t confuse it with the Jurançon AOP, which produces either dry or sweet white wines next to the city of Pau, and in which Jurançon blanc grapes are not allowed! I know, I know, it’s complicated.

Mauzac Blanc: Rarely used for Armagnac, but quite common in wine production around the town of Gaillac, not far from Toulouse.

Mauzac Rose

Meslier Saint-François

Distillation is also different. While in Cognac, it is often the winemaker who distils, or at least brings his wine to a small village distillery, in Armagnac, very few producers have their own still, and they instead rely on people called bouilleurs ambulants; or itinerant distillers. They go from one winery to the next during the distilling season, bringing a mobile still on a trailer. This means that, while it isn’t prohibited, Armagnac is very rarely pot distilled, and rather uses small, wood fired columns, usually no more than 3 metres high, worm-tub condensed, and with usually less than ten rectifying plates.

While as whisky enthusiasts we’ve come to grow wary of column stills, the Armagnaçais column is actually quite different. It works on the same principle, but its small size implies a very low degree of purification in the spirit. Armagnac leaves the still at between 52 and 62% alcohol, which actually means that a double distilled Cognac will technically be purer and have less body. Now, stop typing, this is a massive oversimplification. Other parameters like cut points, grape varieties, terroir, ageing and the presence of lees during the distillation process have a say in all that. What I’m basically saying is: yes it’s column distilled, but it’s also very tasty and not at all a neutral, über-purified spirit.

Armagnac is then aged for at least one year in European oak, starting from the 1st of April following the date of harvest. VS and VSOP bottlings exist, but, opposite to Cognac, it is the custom for Armagnac to be released vintage by vintage. Quite often a part of a cask will be bottled as a vintage, and the remaining part will be left to age.

Armagnac, like Cognac, is composed of different subregions, three to be precise:

Bas-Armagnac: The most famous subregion, it is where the majority of vineyards dedicated to Armagnac production are located. The terroir here is famously called “sables fauves” (tawny sands), a mix of sand and clay, giving delicate and pure eaux-de-vie.

Armagnac-Ténarèze: A terroir made less of sand and more of limestone covered with a variable thickness of clay, it gives spicier and bolder eaux-de-vie.

Haut-Armagnac: There are these days only small isolated vineyards in the Haut-Armagnac subregion, as most fertile lands have been converted to cereal crops or cattle farms. There are however a few good quality producers in the region, like Chateau Arton, which farms biodynamically.

All of this is great, but what should I buy?

As with my piece on rum, I’m writing this as a quick cheat sheet and an Armagnac-Cognac buying guide, based on my own opinions and specifically aimed at the typical Dramface reader and educated whisky consumer.

That means that while the French brandies easily accessible to us might be from famous brands like Hennessy, Rémy Martin or Hine, I would not advise buying them. In all honesty, they are rarely bad, but even more rarely exciting. As in Blended Scotch production, most of these big players use “harmonisation” methods such as caramel colouring or dosage (light sweetening). Thus, the brandies they produce are aimed, depending on the price, either at the casual drinker/cocktail maker, or the well-heeled but less invested occasional drinker/buyer.

So what should we buy dear reader? Well, the real answer is: nothing. Buy Armagnac or Cognac only if we have the means and actually want to, not because a pseudonym on the internet told us to. Try drams at bars if we get the chance, by all means, but we’re all grown-ups, we already know that.

So here’s a quick list of a few producers worth looking into. I’m afraid I can’t check the availability of those in every market, but Cognac is usually pretty widely distributed. Armagnac might be a bit tougher to find if you’re not in Europe.

Cognac:

Grosperrin: the OG Cognac independent bottler. Despite not owning vineyards themselves, everything they bottle is great, from super old single cask, cask strength rarities down to their basic VSOP and XO, bottled under the brand Le Roch, which are really well priced as well. Always unsweetened, uncoloured and unfiltered.

Jean-Luc Pasquet: They bottle Cognac both from their own vineyards and from casks they purchase. Older vintages are often released at cask or at least high strength.

Through The Grapevine: A Cognac independent bottling brand, managed by la Maison du Whisky and Velier. Only cask strength, unadulterated small batches. Can be pricey, but often less than whisky of the same age.

Fanny Fougerat: Really elegant Cognacs, a good core range and the occasional high strength, single cask bottling.

Delamain: The only big house I’ll allow here, as even if the price is often high, their small batch bottlings at 45-50% ABV are definitely expertly crafted.

Lhéraud: Lhéraud has been owned by the same family for more than a century, and they distill only from wines they produce. They also own the Baron Gaston Legrand brand in Armagnac.

Vallein Tercinier: High quality producer, the vintage bottlings are bottled at cask strength.

Prunier: Very High-end vintage bottlings.

Mauxion: same same.

Malternative Belgium: An independent bottler specialised in Cognac.

Swell de Spirits: A French indie bottler, they release Cognac, Armagnac, but also whisky, rum or Mezcal. Good stuff, if a little pricey sometimes.

Grape of The Art: Another Cognac-focused indie.

Asta Maurice: Asta Morris’ Cognac & Armagnac branch.

Decadent Drinks: Angus and the DD team have bottled a few Cognacs and Armagnacs over the years, often from Guilhem Grosperrin’s cellars, and always high quality.

Michel Forgeron: Small producer in Segonzac, very high quality.

Jean Fillioux: Brilliant from indies at higher strength.

Lots of indie bottlers have dabbled into Cognac or Armagnac at some point, often with great success: Cadenhead’s, Dram Mor, Watt Whisky, Thompson Bros… I even spotted a 30yo Early-landed brandy bottled by the Good Spirits Company in Glasgow when I was there, and for a good price. There may be some left.

Armagnac:

Armagnac is the best value spirit on earth when looking for well-aged or vintage bottlings. Period. I’ll give you some examples of both estates and indie bottlers, as you can only try some of the former through the latter sometimes. Quick sidenote, when I say higher strength talking about Armagnac, it can mean ABVs as low as 43-45%, as it is often barrelled at around 55%, so there isn’t much left after 30 or 40 years in cask.

Domaine de Saoubis: a biodynamically farmed estate, producer of great spirits. Usually available through indies.

Domaine D’Aurensan: Crazy good value Armagnacs, they produce from their own vineyards and grow all ten allowed grape varieties, which is extremely rare.

Domaine du Tariquet: They’re more famous for budget wines, but they also produce some good value Armagnac. Forget the classic VS, VSOP and so on, go to the small batch bottlings at higher strength. A good place to start.

Domaine Laballe: Again, some good value Armagnacs to be found here.

Dartigalongue: Usually heavier on the wood, but great value, even for Armagnac. They have a range meant to be used in cocktails too if that’s something you dabble into.

Zero Nine Spirits: A French indie bottler, which like Swell De Spirits, bottles Armagnac, but also rum and whisky regularly.

ROW Spirits: indie bottler.

Hootch: French indie bottler specialising in Armagnac.

Le Passeur: another top-class Armagnac indie bottler.

Domaine de Pellehaut: High quality estate.

L’Encantada: Another Armagnac indie bottler, which I believe might be easier to get overseas thanks to distribution handled by la Maison du Whisky.

Hontambère: A great estate offering some really good value high strength bottlings.

Poh! Spirits: Another great bottler.

Darroze: Quite a famous name, in Armagnac as in cooking. As always, look for natural strength bottlings.

Version Française: La Maison du Whisky’s brand for independently bottled Armagnac and French whiskies.

Domaine de Charron: A great producer, which tends to bottle their vintages at cask strength.

Château de Gaube: I love their Armagnacs for the fruity notes.

There are countless more great producers and bottlers, and honestly, once you go past the entry level, supermarket cheap stuff, the average quality level in Armagnac is pretty damn high in my opinion.

Now, like last time, let’s conduct a little interview before writing some tasting notes.

Serge Valentin

Serge is of course famous for being the person behind the whiskyfun.com blog. He is a world-renowned single malt Scotch whisky connoisseur and keeper of the quaich, he also regularly tastes Armagnac and Cognac, as well as rum and other spirits on Sundays; Whiskyfun’s malternative day. Writing this interview, I also realised he has somewhat appropriate whisky initials!

AF: What do you think really marks the difference between Cognac and Armagnac?

SV: I think it mostly depends on the style of the brands and the era of the bottlings. Among the traditional houses, I’d say Armagnacs tend to be more rustic, more “terroir”—whatever that may mean—whereas Cognacs are more refined and fruitier. Let’s say prunes and coffee versus peaches and yellow flowers. But I find that, increasingly, the two categories are converging, perhaps due to the internationalisation of tastes, which are becoming more and more similar, maybe under the influence of… whisky!

AF: Is the average quality level in Cognac & Armagnac really higher than in single malt whisky?

SV: Hard to say, really, as I don’t go out of my way to taste entry-level Cognacs or Armagnacs, especially from the big houses. They’re a bit like mass-market blended Scotch, decent enough, but nothing to write home about. That said, at the same price point, say between €100 and €200, then yes, absolutely, Cognacs and Armagnacs are on a whole different level compared to single malts. Oh dear, I’m probably making more friends again...

AF: What things that are common practice in French brandy production do you think the Scotch whisky industry could take inspiration from?

SV: I’d say it comes down to the ageing methods and the choice of casks. In particular, more whisky producers often aim to reach the desired age statements (or the minimum required age) using inactive casks, then ‘season’ the spirit in the final months with wine casks, new oak, or other first-fills. To me, this sometimes results in things that feel disjointed or not fully integrated (“grape or grain, but never the twain”, right?), even if their processes do seem to be improving. These days, there are some excellent ‘finishers’, and others who just don’t seem to get it right. By contrast, in French wine-based brandies, active casks are generally used at the start of the ageing process, until the desired ‘additive’ ageing effect is achieved, then the spirit is transferred to less active casks, refills, known as ‘fûts roux’, for the more ‘interactive’ stage of the ageing process. Not to mention demijohns. I suppose it would be great that the Scots would do more of that too.

AF: In your opinion, what should a seasoned whisky enthusiast look for when browsing for Armagnac or Cognac?

SV: Turn to the smaller producers, especially those that are own-estate and grow their own vines, but also the top-quality aging houses (négociants éleveurs). With grapes and wine, terroir plays a far more important role than with grains imported from anywhere.

AF: Do you have particular Cognac and/or Armagnac producers to recommend?

SV: Yes, the very same houses that independent bottlers, across the world, have already chosen anyway. They do an excellent job of selecting them! I think the list of my tasting notes gives a fairly good reflection of my tastes, my favourites are the ones I sample most often, which is far less the case with whiskies or rums, where I try to be a bit more representative of the market. But readers don’t always realise that—ha!

AF: Have you tried wine-based brandies made in other regions, and if so, have some impressed you with their quality?

SV: Indeed, what are known as fines, but I find they rarely reach the level of the best Cognacs or Armagnacs, both fines as well naturally. Marcs, which are distilled from already-pressed grapes rather than from wine, are often more interesting, such as certain Marc de Bourgogne, Marc du Jura, Marc de gewurztraminer in Alsace, Italian grappa, and so on.

AF: Since everyone knows you enjoy Cognac, Armagnac, rum and whisky of course quite a lot, I’m going to ask you if there are other drinks you enjoy, spirits or not?

SV: Sure, great mezcals, teas, eaux-de-vie, and of course wine, my first love. For me, it’s more that spirits are the alternative to wine, rather than the other way round. I’m currently getting into cold-brew teas, which I’ve just discovered in China. It's quite fascinating!

Many thanks to Serge for kindly agreeing to answer these questions. If you haven’t done it already, leave the rock you’ve been living under and take a look at his tasting blog, whiskyfun.

Review 1/3

Arbellot De Vacqueur Lot 67, Cognac Bons Bois, Through the Grapevine, 55yo, indigenous fermentation, 1967 vintage, non-chill filtered, natural colour, 52.4% ABV

£178, (€215) paid without regret

I had been yearning to own a great Cognac for a while, and I wanted something that would tick all the boxes: cask strength, natural colour, no sweetening, and no chill filtration. I stumbled upon this one day and couldn’t believe the price vs. age ratio, which is very good, even for Cognac. I did buy it and have no regrets.

Score: 9/10

Exceptional.

TL;DR

Value doesn’t necessarily mean cheap: case in point

Nose

Fruity, fermenty, and intensely aromatic. Unique nose, thanks to, I think, indigenous yeast fermentation. Grapes, cherries, bread dough, dry lavender. Tobacco leaves, raisins. Damp cellar. Aged earl grey tea. Buddha’s hand zest.

With water: More herbal, with dry mint. Some dark chocolate shavings.

Palate

Flavourful, eventful, evolving. Fruity and winey attack, with a balancing acidity, turning into a beautiful bitter liquorice finish. Absolutely lovely.

With water: Spicier, more about the cask, or rather age, echoing the nose.

The Dregs

This is a gorgeous, humbling spirit. I feel like I’m missing so much stuff. This is beautifully complex. This Cognac is not only older than me, but also older than both my parents. I’ll cherish this bottle.

Score: 9/10

Review 2/3

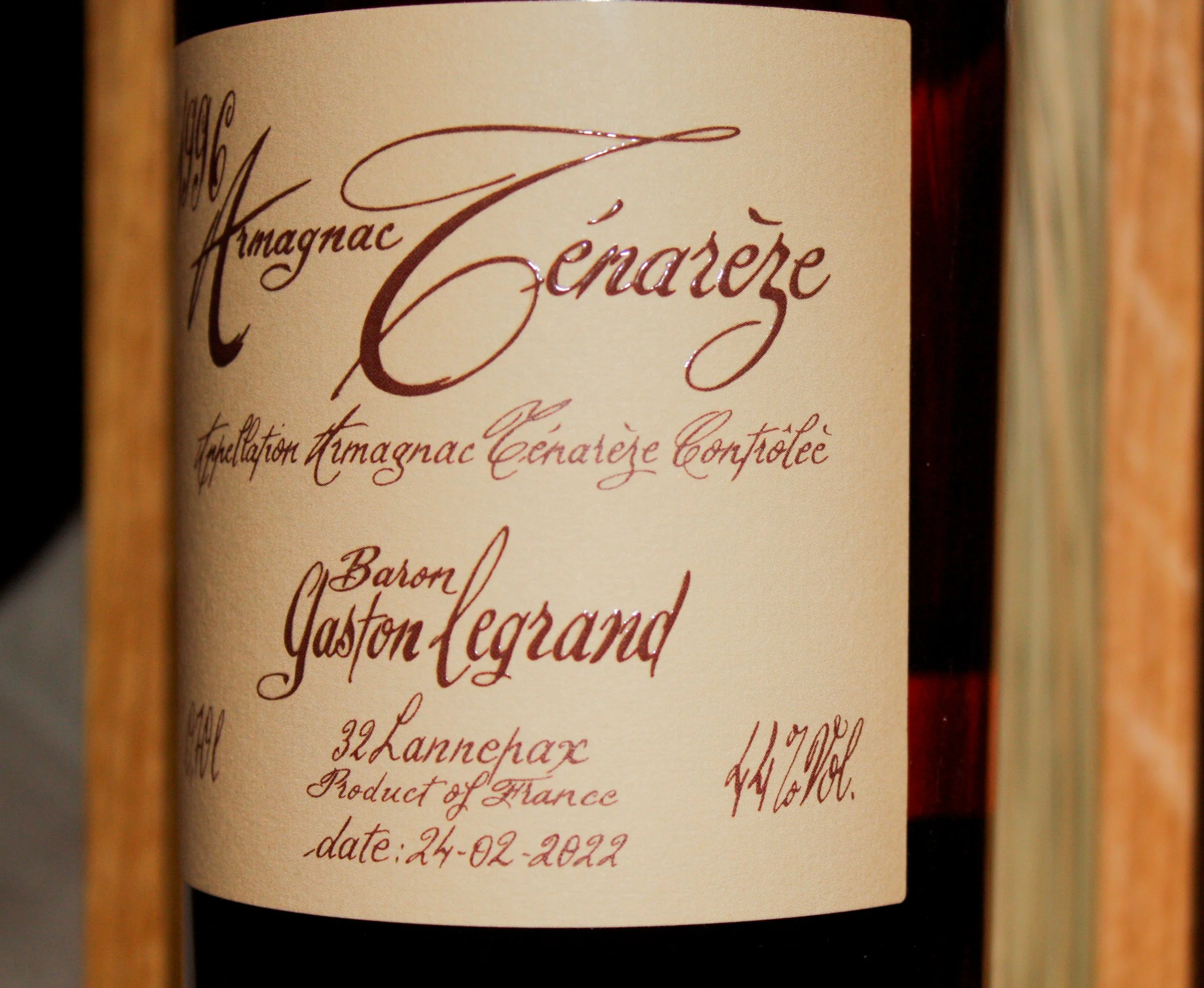

Baron Gaston Legrand, Armagnac-Ténarèze 1996, bottled 2022, 26yo, 44% ABV

£100, (€120) paid

Similarly, I also wanted a nice Armagnac, and I have a little obsession with birth year bottles. An opportunity at work allowed me to get this at a good price, but you’ll very rarely pay over £150 for 1990s vintages of Armagnac.

Score: 7/10

Very good indeed.

TL;DR

Want a birth year bottle? Buy an Armagnac like this

Nose

Fruity as well, but not tropical. Dried peach and apricot, alongside wood spices and sandalwood. Chicken broth. Bacon glaze. Caramel sauce and Grand Marnier.

With water: a bit darker, with ginger and a hint of liquorice.

Palate

Rich, spicy, as a good Ténarèze should be. Age shows. Pure dark chocolate, liquorice, and orange oil. Lingering herbal bitterness.

With water: Doesn’t really swim well. It doesn’t fall apart, but it loses precision. The finish becomes a bit more tannic.

The Dregs

This is a very solid Armagnac. It is typical of a Ténarèze and as such maybe not the easiest style of Armagnac, but still, an example of the incredible value this spirit can offer.

Score: 7/10

Review 3/3

Baron Gaston Legrand, Bas-Armagnac 1985, 39yo, 40% ABV

Sample

This one is from a sample. It is reduced to 40%, but no colour or sugar is added. I don’t know about chill filtration, but even when employed, it tends to be minimal in Armagnac.

Score: 7/10

Very good indeed.

TL;DR

Straight from the jungle of France’s South West

Nose

Tropical fruits burst out of the glass! Ripe mangos, guava, and cooked pineapple. Muscat de Rivesaltes, and light, floral honey. Apricot nectar and ripe yellow nectarines. Gorgeous nose.

With water: Ultra ripe melon appears, along with a hint of roasted coffee beans and heavy cream.

Palate

Stays on the fruity train. Dried tropical fruits drenched in sweet wine and maraschino liqueur sauce. Very light tannins. Old Jurançon wine. It does feel a bit light, but it is still bursting with flavour.

With water: Loses definition on the finish, but stays balanced and flavourful.

The Dregs

I would have loved to try this at full blast, but alas, another time maybe. Even at 40%, this is immensely enjoyable. At around 45%, I probably would’ve awarded it another point or two. The nose is simply divine.

In the end, I hoped you enjoyed this lengthy ramble, and that you got something from it. I’m planning on writing one last one about all the other spirits I’ve not yet mentioned. For now though, I’ll enjoy the holiday break, maybe with a glass of nice brandy. À votre santé!

Score: 7/10

AF

-

Dramface is free.

Its fierce independence and community-focused content is funded by that same community. We don’t do ads, sponsorships or paid-for content. If you like what we do you can support us by becoming a Dramface member for the price of a magazine.

However, if you’ve found a particular article valuable, you also have the option to make a direct donation to the writer, here: buy me a dram - you’d make their day. Thank you.

For more on Dramface and our funding read our about page here.